Consolidated Homeowner-Built Housing: Why Is It Important?, by Peter M. Ward

It’s important because most working-class populations today live in these low-income neighborhoods that have built up over 20 to 40 years but with densification and intensive use are falling into decline, and in urgent need of sensitive housing rehab (rehabilitation) policies and progressive community revitalization strategies. The problem is that in many cases the agenda of planners and policy makers is focused elsewhere: urban redevelopment and neighborhood renewal projects which invariably lead to clearance and population displacement—an enduring planning challenge in both the South and the North. The focus of the Latin American Housing Network is to analyze the nature and dynamics of consolidated settlements, and to explore how they vary across cities and contexts.

What are Consolidated settlements?

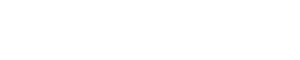

Low-income informal settlements known as favelas, loteos populares, loteamentos, barrios, campamentos, and colonias populares have been the primary form of low-income housing production for working class populations since the 1960s. Most settlements began through land captures called invasions/occupations or illegal land subdivisions. Built through self-help and community action, individual properties were gradually built-out and these larger settlement areas “consolidated” over time.

These dwellings began as shanty structures on individual lots devoid of infrastructure, and settlements were progressively transformed as residents self-built their own dwellings as their resources permitted, and as city and state authorities slowlyextended basic services into the settlements — a process that invariably took 15-20 years to complete. Until the late 1990s and the promotion of mass social interest housing, policies to improve conditions in consolidated settlements generally comprised “upgrading” and title “regularization” policies that mostly supported consolidation processes since they integrated erstwhile ‘slums’ into the fabric of the city.

Yet yesterday’s consolidated settlement have often become physically distressed, and if they were not slums in the past, without concerted policies of rehab and revitalization they threaten to become slums in the future. Dramatically increased population densities (400-500 persons per hectare) and intensive usage by residents over time means that basic infrastructure is often breaking down and buildings are deteriorating. To make housing habitable and safe amid changing household structures and evolving housing needs, these consolidated homes often require remodeling, modernization and regeneration.

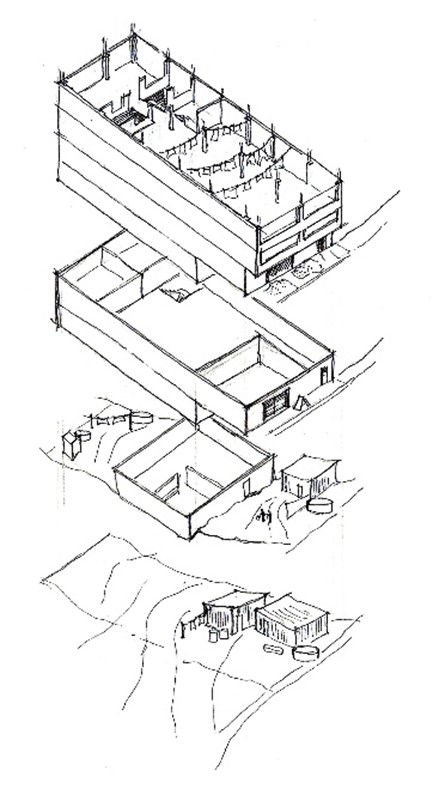

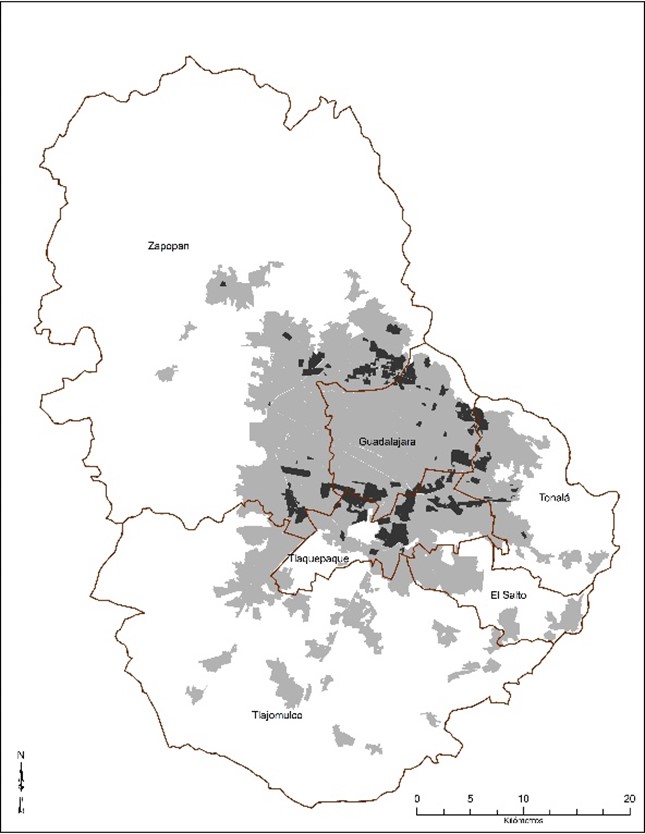

Where are consolidated settlements?

Think of consolidated settlements as Latin America’s first suburbs: neighborhoods that are no longer on the city periphery but occupy what are now well-serviced locations relatively close to the city center, where decades of public investment offer prime access to public services and public transportation. Spatially equivalent to the “first suburbs” in North American cities, Latin American inner suburbs (“innerburbs”) offer a strategic opportunity for policy makers to counter urban “sprawl” into more distant rural and peri-urban zones. However, the problem is that most policy makers are largely ignorant of the ongoing needs of the populations living in today’s consolidated settlements, nor are they aware of the levels of physical deterioration that exist.

This is the focus of the Latin American Housing Network’s collaborative research across ten countries and over a dozen cities, which for more than a decade has used methodologies that seek to reveal the everyday dimensions of such household and community organization, and to better understand the dynamics of how to relate to broader urbanization processes, and to the future challenges for housing policies and planning.

Principal LAHN Findings and Arenas for Ongoing Research

The collaborative research has generated important findings that offer important directions for ongoing research about consolidated informal settlements.

Densification and the Rise of Non-Ownership especially Renting.

High population density as original young pioneer self-builders raised their families, shared with kinsmen, and as informal rental housing opportunities were created through a variety of petty-landlord tenant arrangements. Against the backdrop of the rise of renting in consolidated settlements patterns of rental housing supply and demand are important emerging priorities today.

Changing Household Structures and Social Mobility.

One of the most striking findings from the LAHN studies is that the majority of pioneer or first arrival self-builder owner households still live in their lots: 20-30 years continued residence and spatial immobility are the norm. Starting as classic “nuclear” family structures, contemporary household structures are often “extended” or “compound” (adult children and grandkids sharing the lot as separate households). Adult children raised in the barrio have higher levels of education and some are upwardly mobile socio-economically, but many remain poor and either rent nearby, or opt to live long term on their on their parents’ lot.

Unlike the sedentary and long-term residence for owners, owners, renters show high levels of spatial mobility (“churn”).

Depending upon the location and the level of consolidation, some better off families and small commercial enterprises do engage in buyouts resulting in some “pocket gentrification”. Commerce is most likely on corner lots and along main streets.

Aging, Household Organization and Informality.

On larger lots and dwellings sharing is commonplace. Faced with limited possibilities for ownership elsewhere, some 2nd and 3rd generation (now adult) children see inheritance of their parents’ lot and home as a future long term housing option for homeownership.

Aging, and increasingly the passing of elderly parents together with the lack of inheritance planning and adjudication is leading contested downstream ownership and the “clouding” of (formally) clean titles that have often been provided by local authorities through programs of tenure regularization. This has repercussions for informal property sales at market value, as well as the incentive of adult siblings who do not have title in their names to engage in housing rehab and investment;

Dilapidation, and Deterioration of the Physical Environment

LAHN observations in different cities led to an awareness about the need to differentiate between the potential for successful physical rehab on different types of consolidated settlements (favelas and villas which generally have smaller modal lot sizes, compared with colonias populares and barrios which typically have larger lots as well as more regular settlement layouts and grid street patterns. Rehab is more difficult on congested and irregularly shaped block and lots.

Informal renting and sharing lead to high levels of lot overcrowding and physical dilapidation.

Dwelling structures born of gradual self-built expansion by the pioneer nuclear household are often out of synch and inadequate to meet the needs of multi-generational household (lack of privacy, overcrowding, etc.). Indeed, secondary housing units were often much worse than the parental unit (material structure, number of rooms, sanitary facilities, etc.) Aging and heavily deteriorated consolidated settlements may feature a “slumification” processes and trajectory.

Despite being of poor or mixed quality of physical construction, homes today have a relatively high “exchange” (potential sale) values (US$ 50,000-100,000), and yet the asset is effectively frozen from the market by its ongoing “use value” for adult children and grandchildren, and by a lack of financial policy supports for buyouts.

Three levels of physical revitalization are identified by the LAHN studies: micro (dwelling and lot); meso; which is the street and the intersection between private and public spaces; and macro/local which is the public space of the community.

What is the future of consolidated informal settlements?

In the 2016 volume Housing Policy in Latin American Cities: A New Generation of Strategies and Approaches for 2016 UN-Habitat III , our primary interest is to explore a range of detailed policy approaches for Physical Rehabilitation; Financing Tools; Legal and Regulatory Initiatives; and Social and Community Mobilization.

We very much look forward to receiving comments to this blog as well as learning about comparable or different experiences.