One Building at a Time: Rental Housing for Community Revitalization, by Kristine Marie Stiphany

Rental housing is the new upgrading

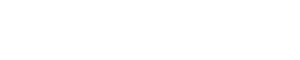

Since the 1980s the ‘upgrading’ or revitalization of informal settlements has been done through the addition of basic infrastructure, utility services and multi-family buildings designed by engineers and architects, as an alternative to the strong focus on mass housing schemes of the 1970s. The idea was that progressive “in-situ” interventions like those shown in Figure 1, below, would make the difference between the formal and informal city disappear.

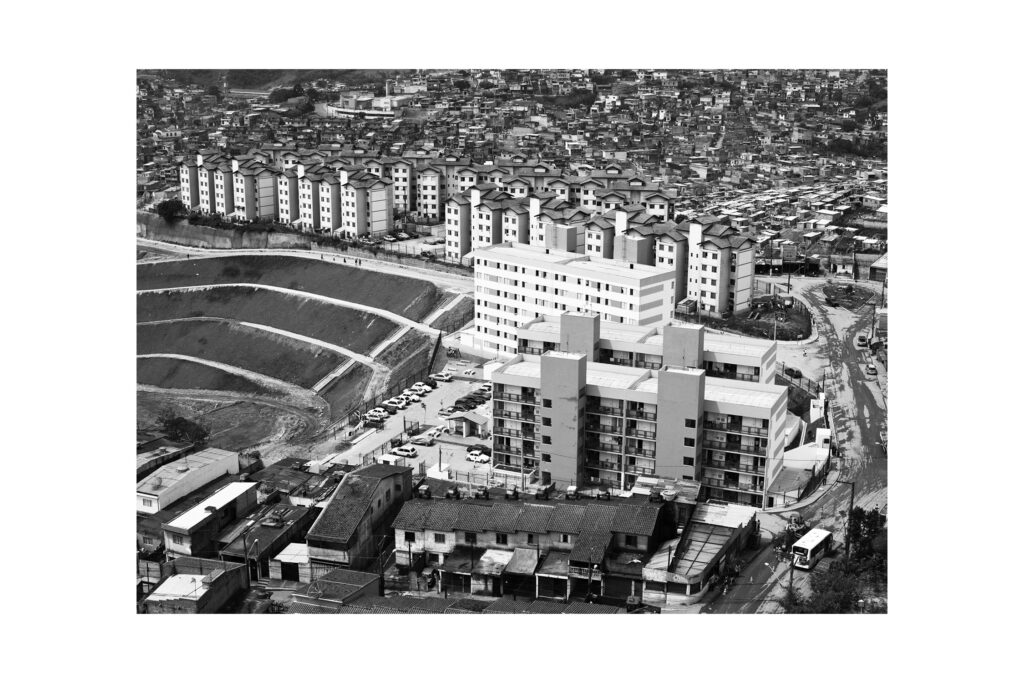

Fast forward several decades, and disciplinary fields of the built environment have made little impact on stemming the reproduction of sociospatial inequality in cities (Roy, 2005; Perlman, 2010). One missed opportunity is the revitalization already happening at the level of individual properties, where many original homesteaders are forming investment and construction partnerships that integrate apartment additions into their dwellings—through expansion or by building anew—as shown in Figure 2, below.

The rental turn in Latin America has intensified over the past decade (Baqai and Ward, 2020), but these modalities of informality in Brazilian peripheries are an evolution of tenement cortiços in industrializing cities at the turn of the 19thto 20th century. When rent controls suppressed the cortiços in the 1940s, they simultaneously primed informal land and housing development on urban peripheries (Sampaio, 1994; Bonduki, 1998), as the cost of land at the urban margins was cheap and incoming rural migrants sought the dream of homeownership, so the consolidation of dwellings was associated with social capital and prosperity. This first generation of informal settlements called loteamentos (allotments) set the stage for the rise of Brazil’s second type of settlement, the favela, amid mid-20thcentury mass urbanization. The built environment of both settlements evolved as residents progressively built to promote intergenerational living arrangements and space sharing among families. Collective urban management or “autogestão” became important for reinforcing tenuous ties to land in these early settlements as residents built a refuge from the high costs of inner-city rental housing (Kowarick and Ant, 1988).

Urban researchers are just now beginning to look at impacts of upgrading on informal settlement growth in Latin American cities. In the 1970s, the Brazilian architect Carlos Nelson Ferreira dos Santos advocated for informal settlement contextualism, as opposed to modernism, suggesting that the housing landscapes that residents of informal settlements make themselves are superior to the exogenous types to which many were (and still are) subjected by governments. A housing system that is built incrementally consolidates to create diversity in its internal environment while creating mutually beneficial relationships with the external. Although planners and architects who design upgrading projects tend to believe that intervening in informal settlements constitutes contextualism, there is little evidence to suggest that they are working with informal settlements to meaningfully include the contributions of existing built environments in sustainable community revitalization strategies. Rental is an opportunity to correct upgrading’s limited course.

The origins of micro-revitalization

In fact this was the idea all along. When incremental housing first gained momentum in policy and planning, the thinking of architects and urbanists like Sergio Ferro in Brazil and John Turner in the United States influenced key projects based on the idea that small increments added to buildings can lead to dramatic urban results and sustained change. Peru’s PREVI housing was based on incrementalism, and Pritzker prize winner Alejandro Aravena made a career by repackaging this idea into his Elemental Housing decades later.

The premise of what came to be known as sites and services or “core housing” models was to establish a physical parameter (e.g. the lot, a modest one-room house, or what Aravena termed a “half house”) that could be progressively scaled up by individual families as broader community consolidation gained momentum. What none of these early authors considered was how much economic uses would be interwoven into the fabric of what has been predominantly homeowner-occupied housing.

São Paulo offers a key example. Recent research shows that rental units in one typical consolidated settlement exist on more than 50% of properties (Stiphany, Ward, and Perez, 2022). Yet these rental units create both opportunities and obstacles. They are affordable compared to formal urban areas; are flexible and allow residents to adapt their housing situation to changing circumstances; feature low economic entry barriers; and are supported by local community networks of investors, builders, and renters. At the same time, they contribute to overcrowding of what were essentially single-family (albeit intergenerational) homes and further strain already-fragile infrastructure systems, which can lead to poor living conditions that adversely affect health and quality of life; insecure tenure can make residents vulnerable to eviction or displacement by authorities or landowners, and without formal leases, renters may face increased challenges accessing credit and social services; and uncontrolled building densification can make buildings prone to decay and deterioration from disasters, and residents less likely to escape from them.

The complex, intersectional nature of rental densification may be why renting has never occupied a serious place in “slum upgrading” programs in Brazil and elsewhere.

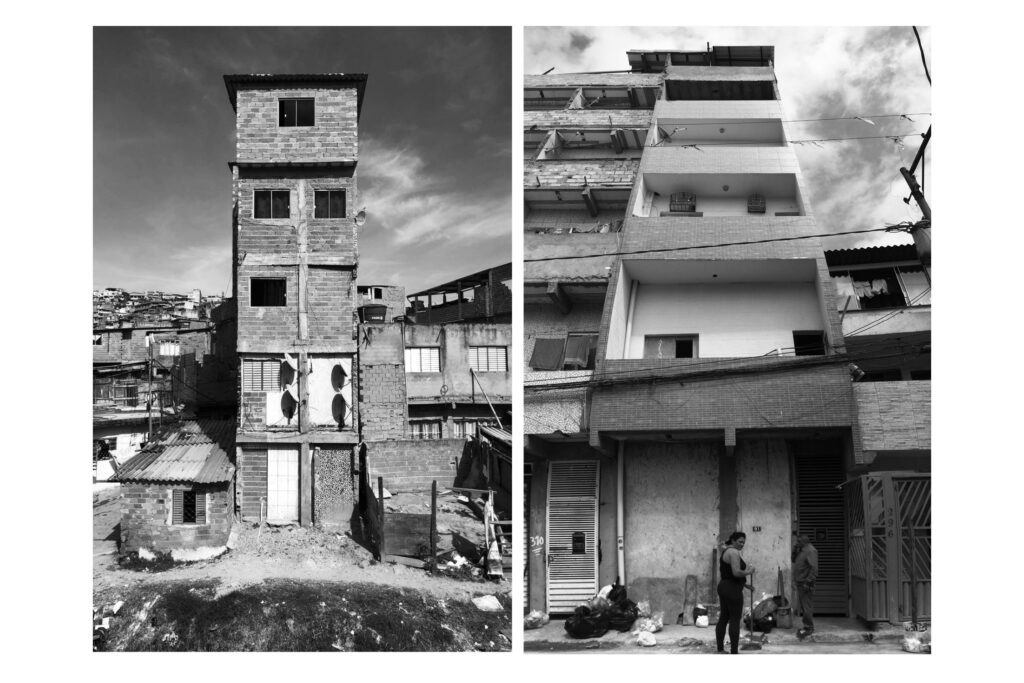

In a recent study about renting in São Paulo, I suggest how to guide the next generation of urban redevelopment by revitalizing and/or reconstructing five tenure arrangements observed in the following material forms illustrated in Figure 3, below: (1) a homestead preservation process, resulting in modest buildings where homeowners and renters are mixed; (2) an exit strategy, in which homeowners reduce their footprint in homesteads to maximize rental space; (3) an entrepreneurial project that entry-level investors undertake together that could not be readily done alone; (4) a slumlord cluster of degraded and highly precarious apartment houses; and (5) total reconstruction of a former shack (Stiphany, 2023). Across these examples, rental and owner units interact in ways that invert the previous dominance of homeownership-occupation in informal settlements, in ways representative of dense, inner-suburban and lower-density peri-urban contexts.

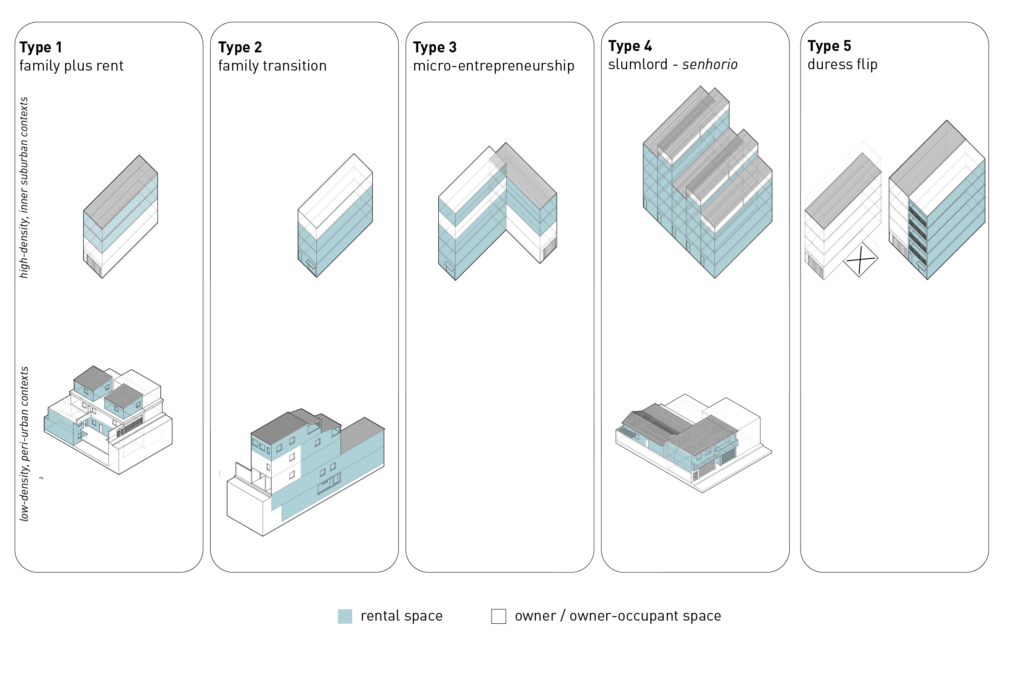

Some types (1 and 2) are reminiscent of original dwellings in shape and with the sustained presence of an owner living on site. Other building revitalizations, represented by Type 5 pictured above, in which external investors erase all semblance of the past with mixed use buildings, emulate processes of the formal city, as shown in Figure 4, below.

Some of these buildings (particularly Type 5) are of high-quality construction, having been built according to standardized building systems within relatively short timeframes (six months), and they could be used as generalized models for revitalizing other derelict properties. However, while landlords maintain the affordability of some apartment buildings, many are out of reach for most renters. More research is needed about how degrees of rental-mixing across individual properties add up to an overall revitalized and housing-accessible community.

The potential of rental housing for community-revitalization

Rental revitalization is one example of residents reinforcing their praxis of homebuilding while also using economic development to hedge against future uncertainties. It reflects a next generation informality in which buildings have radically morphed in response to so called “formalizing” planning and policy decisions. The smaller scales of upgrading that result provide a basis for reorienting the role of urban planning in informal settlements, with several lessons for what such change should entail in practice. Planners and policy makers should: First, promote redevelopment through adaptive reuse rather than the new construction of large-scale, exogenous building types. Second, understand density as an evolving mobility (and potential forced mobility or immobility) through improved situated analyses of existing housing environments and occupant needs. Third, encourage some types of rental accommodation while prioritizing renovation of others with land regularization and building preservation. Fourth, conceptualize economic uses as what Harris (2018) refers to as an embedded informality. Given that so many places where rental is embedded in built environments involves informality, surely planners and policy makers should be able to deploy rental as Harris suggests, in order to create contexts for cooperative living, without creating others for gentrification.

References

Azhar, A, H Buttrey and PM Ward (2021) ‘Slumification’ of Consolidated Informal Settlements: A Largely Unseen Challenge. Current Urban Studies 9: 315 – 342.

Baqai, A and PM Ward (2020) Renting and Sharing in Low-Income Informal Settlements: Lacunae in Research and Policy Challenges. Current Urban Studies 8: 456 – 483.

Blanco AB., VF Cibils, AM Miranda, A Gilbert, E Reese, F Almansi, J Del Valle, S Pasternak, C D’Ottaviano, & I Brain (2014) Busco casa en arriendo: Promover el alquiler tiene sentido. Inter-American Development Bank

Bonduki N (1998) Origens Da Habitação Social No Brasil. Arquitetura Moderna, Lei Do Inquilinato E Difusão Da Casa Própria. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, FAAPSP.

Harris R (2018) Modes of informal development: A global phenomenon. Journal of Planning Literature 33(3): 267 – 286.

Perlman, J (2010) Favela. Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kowarick L and Ant C (1988) Cem anos de promiscuidade: o cortiço na cidade de São Paulo. In L Kowarick (ed.) As lutas sociais e a cidade: São Paulo Passado e Presente. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

Sampaio MRA (1994) O papel da iniciativa privada na formação da periferia paulistana. Espaços e debates 37: 19 – 33.

Roy, A (2005) Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning. Journal of the American Planning Association 71(2), 147 – 158.

Stiphany, K (2023) Vivienda de alquiler informal en São Paulo: una realidad ignorada. (Informal rental housing in São Paulo: An ignored reality). In Vivienda en Arriendo en América Latina. Felipe Link, Adriana Toró (eds.) Centro de Estudos de Conflicto y Cohesión Social – COES; Instituto de Estudios Urbanos e Territorial UC – IEUT UC.

Stiphany K, PM Ward, and LP Perez (2022) Informal Settlement Upgrading and the Rise of Rental in São Paulo, Brazil. Journal of Planning Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X211065495

Ward PM, ERJ Huerta and MM Di Virgilio (2015) Housing policy in Latin American cities: A new generation of strategies and approaches for 2016 UN-Habitat III. Routledge.

Kristine Marie Stiphany, PhD, AIA is an architect, Fulbright fellow and founder of Chapa Studio. Her research and practice encompasses contemporary housing informality and the politics of participatory technologies for urban design in Latin America and along the U.S. – Mexico border. Kristine is an assistant professor at University at Buffalo, SUNY, where she directs the Design with Resilient Environments Lab. She holds a BFA from the University of Michigan, and an MArch and PhD from the University of Texas at Austin.